Osteoarthritis…The Stage 5 Clinger

It's been a while, but let's dive into a topic we've all been dreading: Osteoarthritis (OA). Given its rising prevalence and sticky nature, we’re calling it the 'Stage 5 Clinger' of joint conditions. It may end up being the most relatable blog thus far, given that its prevalence has increased and joint replacement surgery has become commonplace.

It’s become such a global issue that it should be classified as a stage 5 clinger.

Let’s attempt to crash this topic.

***For reference, anything underlined, bolded, and blue is a link to clarify the word/phrase. For example…osteoarthritis.

What is Osteoarthritis?

A degenerative disease leading to the breakdown of the joint tissues: cartilage, articular bone, subchondral bone, synovium, etc.

There are 2 general osteoarthritis diagnoses:

Primary Osteoarthritis - arthritis that develops over time without an identifiable cause.

Secondary Osteoarthritis - arthritis that develops as a result of an injury, surgery, or underlying disease/condition.

Is it an “urgent” issue?

According to a 2020 study, osteoarthritis affects over 300 million people worldwide.¹ Between 1990 - 2017, there has been a 94% increase in Years Lived with Disability (YLD) due to osteoarthritis, and it’s estimated that it accounts for 0.25 - 0.50% of a country’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product).¹ Now, that might not seem like a lot, but last year, the USA’s GDP was $29 TRILLION, which means that in 2024, osteoarthritis alone may have accounted for $73 - 146 BILLION. A separate study put the percentage at 1 - 2.5%, which would be $290 - 725 BILLION.² What makes those estimates more mind-blowing is that they don’t include disease burden outcomes like lost work hours, etc.

What causes osteoarthritis?

…It’s complicated.

Osteoarthritis research has progressed substantially due to the rising prevalence of the condition. Most research focuses on the knee, hip, and hand because these joints are most commonly affected. However, knee OA is the most commonly diagnosed form and may account for 85% globally.³

Research has suggested many phenotypes to classify osteoarthritis, including body part, etiology, distribution (local vs. multi-), pain severity, and more. However, we will focus on 3 general types: ageing, post-trauma, and metabolic.

The “you gettin’ old” type

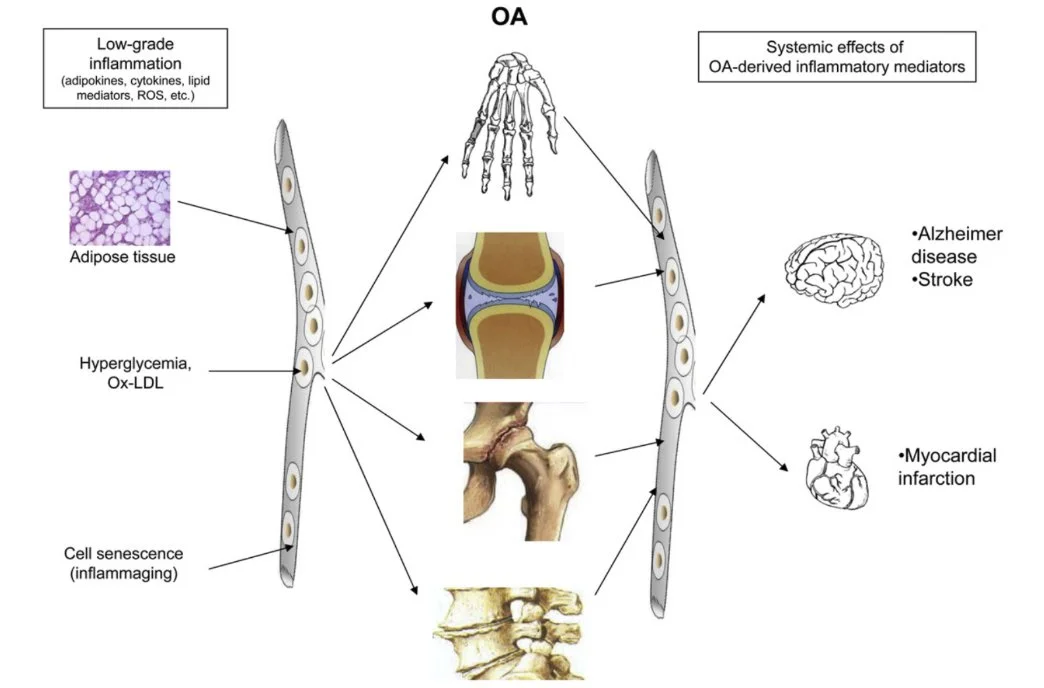

Ageing is the most prominent risk factor regarding OA. OA is associated with both low-grade local and systemic inflammation. And, ageing itself is accompanied by low-grade, systemic inflammation.³

OA is linked to cell senescence.¹ This is when cells stop dividing and spreading but remain metabolically active. Senescence is necessary and protective in many cases. However, as senescence increases with age, it leads to a pro-inflammatory (inflammation-promoting) environment within the joint. Over time, along with other factors, this contributes to the development of the condition.

Ageing is also accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction. This can lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced cellular antioxidant capacity.³ As a result, DNA damage, cell death, etc., may occur, contributing to the breakdown of the joint.

Ageing also results in reduced autophagy.³ Autophagy is like the joint’s internal recycling system. Impaired recycling (which comes with age) leads to cell accumulation, DNA damage, and increased inflammation.

These are just a few reasons ageing increases our OA risk. Unfortunately for us, we haven’t figured out how to ghost Father Time. Therefore, we’re stuck with this risk factor.

The “damaged goods” type

Trauma is considered a modifiable risk factor, unlike ageing. However, I believe it’s more of a hybrid risk factor. Life is chaotic and random, and while you can take steps to reduce your risk of trauma, you can’t completely prevent it.

Trauma includes anything damaging to the joint, including surgery. While surgery is intended to help you, it also comes with many risks, including an increased risk of OA development. Like ageing, all trauma is accompanied by reduced autophagy, which might explain why there’s an increased risk of OA development.³

Articular (joint) cartilage doesn’t divide and proliferate like other tissues of the body.³ Also, articular cartilage is mostly avascular. These two factors make it difficult for this tissue to heal and regenerate when damaged.

In fact, in younger adults who develop OA, the most common cause is previous joint injury.³

The “buffet ate my cartilage” type

“Metabolic” means the “system”, the person, the individual, or the “vessel”. An unhealthy system isn’t optimal for our joints.

This IS a modifiable risk factor. Whether we like it or not, our health significantly impacts the risk of developing chronic diseases. Osteoarthritis is no exception. Simply put, our overconsumption of food and sedentary lifestyles have led to joint betrayal.

According to the NIH, approximately 70% of US adults are overweight or obese. BMI has been shown to have a linear relationship with knee OA and a causal association with OA at weight-bearing joints.⁴⁻⁵ Linear means the higher the BMI, the higher the risk. This is due to two factors: increased joint load and excess body fat, causing chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation. Fat cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines, which is normal. However, when there is excess fat, there are excess circulating pro-inflammatory cells.

In people 65 and older who have OA, more than 50% have high blood pressure, 20% have cardiovascular disease, 19% have dyslipidemia (excess fat cells in blood), 14% have diabetes, and 12% have mental health disorders.²

Being overweight in childhood has a strong association with knee pain, stiffness, and dysfunction in adulthood.⁶

Weight loss has been shown to have a dose-response relationship with knee OA pain and function.² More weight loss means more improvement. Even weight loss from bariatric surgery improves knee OA.⁷

Metabolic syndrome consists mainly of high blood pressure, hyperglycemia (high blood glucose), dyslipidemia, and central obesity. All are associated with an increased risk of knee OA.⁴ It can also lead to impaired bone remodeling, an increase in joint inflammation, and cartilage-degrading activity.¹ And, articular cartilage is particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of elevated glucose and lipids.⁴

Even having a single component of metabolic syndrome, like high blood pressure, increases OA risk almost 2.5x. If you have three components, almost 10x. Having diabetes alone may increase your risk by 40%.¹

No surprise, smoking and alcohol intake significantly increase all-type OA risk.⁶

These categories aren’t exclusive. There are many suspected subtypes and combinations of them. Also, this doesn’t mean that other factors don’t contribute to the development of OA. For example, the role of genetics in OA is estimated to be between 40 - 80%.² 1000s of factors likely contribute to the development of OA: environment, socioeconomics, stress, sleep quantity and quality, and so on.

An Interesting Note…

OA may contribute to the progression of other pre-existing conditions, like cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, autoimmune disease, etc.⁷ As OA progresses, local inflammatory cell production increases and leaks into the bloodstream, exacerbating the pre-existing systemic inflammation. This could contribute to disease progression. Talk about the “circle of life”!!!

This further highlights the importance of being as healthy as possible.

The “wear and tear” myth!

As a physical therapist, I still hear the “wear and tear” phrase from patients and medical professionals alike. However, as you’ve learned, it’s more complicated than we once thought. It’s no longer recommended that we describe osteoarthritis as a “wear and tear” condition to patients, as this gives a false perception of cause.

Let me paint a picture for you…

Rule #5: Never let your knee get between you and a squat.

Being sedentary significantly increases your risk of all types of OA, and even low-intensity exercise may be associated with increased OA risk. Moderate-intensity exercise was shown to reduce OA risk.⁶

People with knee OA spend approximately two-thirds of their time being sedentary.⁸

Regardless of exercise type (aquatic, land-based, muscle strengthening, aerobic, etc.), physical activity reduces pain and improves physical function in people with hip and knee OA.⁹

High and moderate activity levels in both vigorous and moderate recreational activities reduce the risk of OA.¹⁰

People with a history of strength training had a 17-23% reduction in risk for knee pain, radiographic OA, and symptomatic OA. People with the highest exposure to exercise had the greatest benefit regarding OA outcomes. And, adjusting for injury status strengthened the association.¹¹

Yoga, stationary cycling, Tai chi, resistance training, and aquatic exercise were beneficial for patients with knee OA in relieving pain, alleviating stiffness, improving function, and improving quality of life, compared with sedentary controls.¹²

Runners and orienteers had a 54% lower risk of knee surgery for OA than controls.¹³

Adapted physical activity (APA) is the first-line treatment in osteoarthritis. Its benefit/risk ratio is greater than that of drug therapy.¹⁴

Some studies have shown that adults who regularly perform moderate-intensity physical activity have greater cartilage volume, fewer cartilage defects, and fewer bone marrow lesions compared to sedentary controls.¹⁵

Several reviews have shown that recreational running of 25 miles/week IS NOT related to increased risk of structural progression of knee OA.¹⁵

There's no strong or consistent evidence that common forms of physical activity increase the risk of structural knee OA progression.¹⁵

A 2023 systematic review on knee OA came to several conclusions¹⁶:

Significantly higher pain prevalence in non-runners.

No significant difference between runners and non-runners regarding radiographic OA.

No strong evidence to support that OA progression occurs more often in runners compared to non-runners.

No significant difference in risk of future surgery between runners and non-runners.

The point is…

Despite the commonly held belief that running, squats, and exercise in general are “bad” for your joints, there isn’t anything to support this notion thus far. However, there’s context to all situations. As some studies mention, and I agree with this stance, it’s likely that for each individual (considering all factors: health, age, joint integrity, etc.), there is a “happy medium” or “goldilocks” zone of exercise. Doing too little creates a non-optimal environment for your joints and overall health. Do too much and you might progress things more quickly. But, do the right amount, and “yahtzee”, a happy body and joints.

Another False Perception

As I’ve mentioned in a few posts (here & here), just because a pathology (like OA) is present DOESN’T mean it will be painful or disabling. As a society, we have a false perception that structural change to a tissue will hurt. Over the years, more studies have been conducted on asymptomatic populations. Asymptomatic means these people don’t experience pain, and, in many studies, they aren’t limited physically either. These studies have consistently shown that structural changes to tissues are quite common in asymptomatic individuals. From disc herniations, hip and knee OA, rotator cuff tears, meniscus tears, labral tears of the hip and shoulder, UCL tears at the elbow (the “Tommy John” ligament), and the list continues.

For example, we mentioned that knee OA may account for 85% of all OA globally. However, that same study highlights that the incidence of painful knee OA is around 8.1%.³ Another study showed that approximately 10% of men and 13% of women over the age of 60 have painful knee OA.¹⁶ Both studies state that the prevalence of radiographic OA (structural signs of OA diagnosed with x-ray) is higher than the prevalence of painful OA. Another review of people with advanced radiographic knee OA (“bone-on-bone”) showed that 5.9-31.2% of subjects were asymptomatic.¹⁸ Interestingly, the 5.9% group had a higher BMI than the other 2 groups, and knee injuries in this group weren’t accounted for.

The main point here is that though we may see “change” to a joint on X-ray, it doesn’t mean it will be accompanied by pain. More importantly, even advanced OA doesn’t necessarily require surgery. Many papers highlight that the recommendation of surgery for OA should be based mostly on disability and pain, NOT structural change. And, as I tell many of my patients, though surgery is meant to help you, it isn’t 100% certain that outcomes will be good. For example, up to 25% of patients still complain of pain 1 year after joint replacement surgery.² The authors of that same paper state, “Surgery should be reserved for cases in which all appropriate, less invasive options that have been delivered for a reasonable period have not provided adequate symptom relief.” According to many studies, a reasonable period would be 6 months.

Other studies even discuss unhappiness several years after joint replacement surgery, remaining disability, etc. And, don’t forget, all surgeries come with potential complications such as infection, blood clots, and the possibility of death. Sadly, I was on the surgical floor when a patient died a few days after their surgical procedure. While this is rare, you have to understand that these things are possible.

Take Steps to Prevent OA

First of all, you can’t truly prevent OA. There are too many factors that contribute to its development. However, you can try to mitigate your risk by being proactive. Here is what I recommend:

Eat a wide variety of whole foods.

Focus on whole foods like legumes, whole grains, nuts/seeds, fruits, veggies, lean meats, seafood, etc. Eating in this manner provides you with all the macro- and micronutrients needed to support a healthy body, which includes our joints.

Perform moderate to vigorous exercise regularly.

A minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise per week is recommended. This should include at least 1 hour of weight lifting or other form of resistance training to help maintain or improve muscle mass, a vital component of overall health, especially as we age.

For people already suffering from OA of the lower body, low-impact activities like cycling and aquatic exercise may be great options.

Maintain a “healthy” weight and body fat percentage.

The first two steps help in this endeavor.

As we’ve discussed in this post, being overweight or obese isn’t optimal for our joints, and we know it’s not optimal for our health (see this blog for more information). Body Mass Index (or BMI) is the fastest way to determine your current status. While it’s not the best tool, it’s the quickest and most accessible method and works well for the majority of the population.

Knowing your body fat percentage would be great, as it’s likely a better indicator of your overall health. Generally speaking, men should aim for 10 - 20% and women 20 - 30%. This varies depending on your age, physical activity levels, personal preference, etc., but those numbers are a good baseline for the general population. The problem is that body fat percentage is difficult to determine due to many constraints. A DXA body composition analysis is likely best and is cheaper than it used to be, but it’s still expensive, and has limited availability.

Avoid trauma if possible (surgery included).

This is self-explanatory: less trauma, less risk. However, one paper highlighted that knee arthroscopy (such as menisectomy) should be discouraged in people with knee OA, as there’s no strong evidence supporting its efficacy. In fact, these surgeries may lead to an earlier joint replacement.²

Modify activities if you experience severe pain or joint swelling.

High levels of pain and swelling may indicate overdoing it. A recommendation I make is to modify the activity when their pain exceeds a 5 out of 10 either during or up to 24 hours after the activity. This is also true of joint swelling. Modifying activities, NOT avoiding them, helps you keep doing what you need or want without further compromising your health. This can also help you maintain a positive mental state.

Sleep 7 - 9 hours/night.

Some of you may not be able to accomplish this (like my mom…sorry!). However, that doesn’t diminish the importance of sleeping well. 7-9 hours of high-quality sleep is essential for our health, including recovery from injuries, surgery, hard training sessions, etc.

Manage your stress and try to stay positive.

Socialize with those you care about, get outside, meditate, dance…you name it. Anything that helps you be in a more positive mindset is good for your health. Remember, happy body, happy joints.

Quit smoking (or don’t start?) & limit alcohol intake.

Does this need an explanation?

Other potentially helpful recommendations (the previous ones are the bread & butter!):

Warm/hot water submersion.¹⁷

Heat is not only a good pain reliever but may also help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, potential contributing factors to OA development. Also, in people with OA, the water pressure can reduce joint swelling. So, if you live near a hot spring, take advantage!

Certain supplements may help.

Potentially beneficial supplements: Omegas (algae or fish oil), Magnesium, Curcumin (the main compound in Turmeric), Boswellia Serrata (Indian Frankincense), Pycnogenol (pine bark extract), and Collagen.

Like medications, supplements may cause side effects. Most importantly, supplements can negatively interact with medications. So, if you plan to add one to your diet and are taking medications, it’s essential to discuss this with your doctor. Check out our supplement page for our recommendations and affiliate links.

Drink hot beverages.

Interestingly, higher consumption of hot beverages over the lifespan was associated with reduced OA risk.¹⁷ The study didn’t mention why this association existed. My theory is that it likely has nothing to do with the temperature of the drink, but rather with the content of the drinks typically consumed hot. Coffee and tea (including herbal varieties) are the primary hot beverages consumed, each of which has high antioxidant levels. Antioxidants may reduce both systemic and local inflammation, which we’ve discussed is a potential cause of OA. So, drink up!

Conclusion…I DIG IT!!!

Though osteoarthritis may be here to stay, it may not be as bad as we think. While there are things beyond our control, like genetics, there are things we can do to help reduce our risk of developing painful OA or even improve it once it’s clung onto us.

Whatever the case…never leave a fellow craher behind!

References:

Berenbaum F, Walker C. Osteoarthritis and inflammation: a serious disease with overlapping phenotypic patterns. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(4):377-384. doi:10.1080/00325481.2020.1730669

Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1745-1759. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9

Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):412-420. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.65

Du X, Liu ZY, Tao XX, et al. Research Progress on the Pathogenesis of Knee Osteoarthritis. Orthop Surg. 2023;15(9):2213-2224. doi:10.1111/os.13809

Funck-Brentano T, Nethander M, Movérare-Skrtic S, Richette P, Ohlsson C. Causal Factors for Knee, Hip, and Hand Osteoarthritis: A Mendelian Randomization Study in the UK Biobank. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1634-1641. doi:10.1002/art.40928

Luo Q, Zhang S, Yang Q, Deng Y, Yi H, Li X. Causal factors for osteoarthritis risk revealed by Mendelian randomization analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2024;36(1):176. Published 2024 Aug 22. doi:10.1007/s40520-024-02812-9

Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(1):16-21. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012

Ma X, Zhang K, Ma C, Zhang Y, Ma J. Physical activity and the osteoarthritis of the knee: A Mendelian randomization study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(26):e38650. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000038650

Kraus VB, Sprow K, Powell KE, et al. Effects of Physical Activity in Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Umbrella Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1324-1339. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001944

Huang C, Guo Z, Feng Z, et al. Comparative study on the association between types of physical activity, physical activity levels, and the incidence of osteoarthritis in adults: the NHANES 2007-2020. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20574. Published 2024 Sep 4. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71766-9

Lo GH, Richard MJ, McAlindon TE, et al. Strength Training Is Associated With Less Knee Osteoarthritis: Data From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024;76(3):377-383. doi:10.1002/art.42732

Mo L, Jiang B, Mei T, Zhou D. Exercise Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(5):23259671231172773. Published 2023 Jun 5. doi:10.1177/23259671231172773

Timmins KA, Leech RD, Batt ME, Edwards KL. Running and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(6):1447-1457. doi:10.1177/0363546516657531

Daste C, Kirren Q, Akoum J, Lefèvre-Colau MM, Rannou F, Nguyen C. Physical activity for osteoarthritis: Efficiency and review of recommendations. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88(6):105207. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2021.105207

Voinier D, White DK. Walking, running, and recreational sports for knee osteoarthritis: An overview of the evidence. Eur J Rheumatol. Published online August 9, 2022. doi:10.5152/eurjrheum.2022.21046

Dhillon J, Kraeutler MJ, Belk JW, et al. Effects of Running on the Development of Knee Osteoarthritis: An Updated Systematic Review at Short-Term Follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(3):23259671231152900. Published 2023 Mar 1. doi:10.1177/23259671231152900

Diao Z, Guo D, Zhang J, et al. Causal relationship between modifiable risk factors and knee osteoarthritis: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1405188. Published 2024 Sep 2. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1405188

Son KM, Hong JI, Kim DH, Jang DG, Crema MD, Kim HA. Absence of pain in subjects with advanced radiographic knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):640. Published 2020 Sep 29. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-03647-x